It is apropos for part of the next installment of my breed study, though. My dad asked me to fix a couple of holes in a cashmere bag that houses a cashmere throw. It’s a taupe color, and although I have a sizable stash, I have no taupe yarn. Much less cashmere taupe yarn. What’s a girl to do?

Make some, obviously.

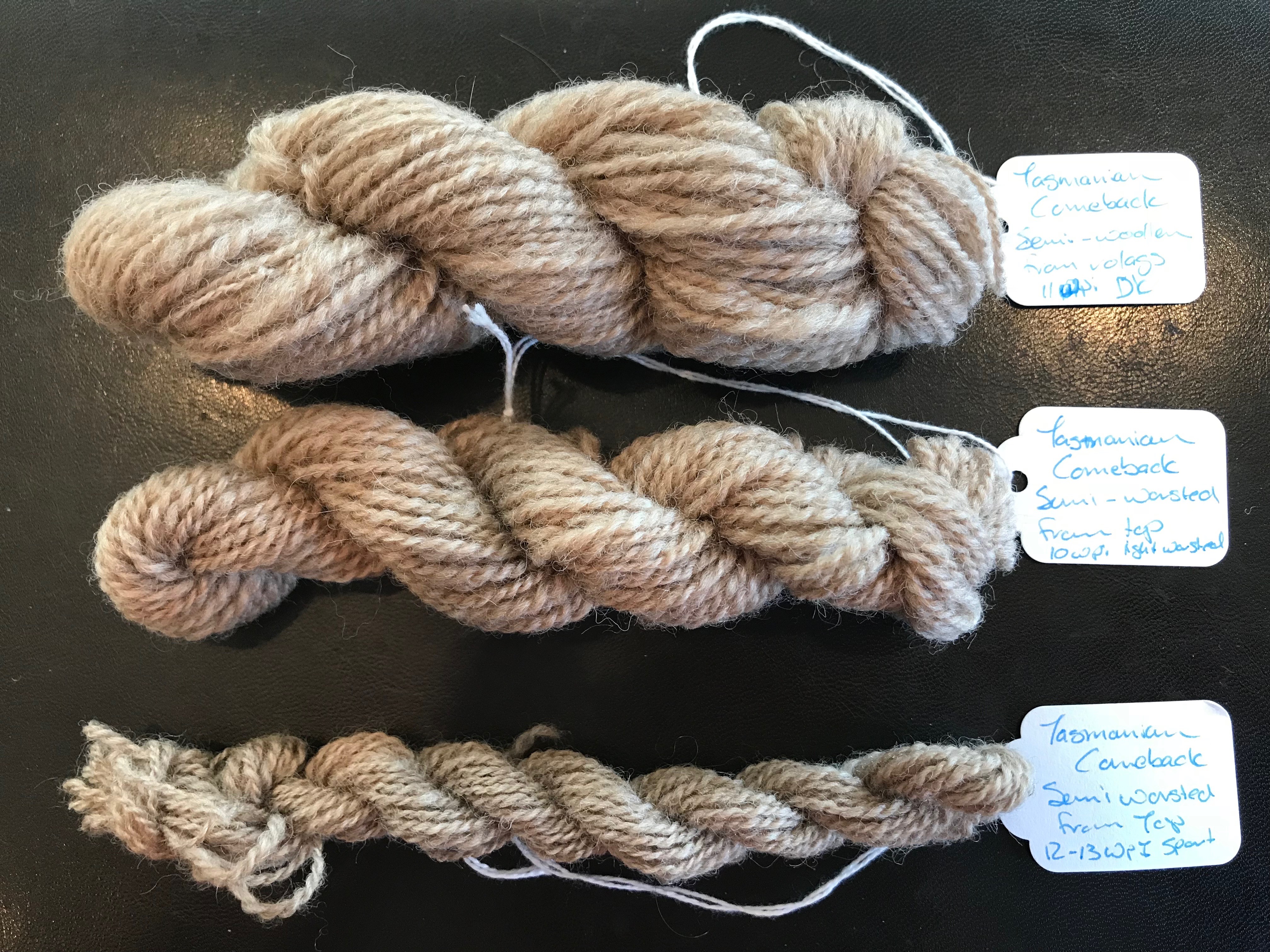

Tasmanian Comeback

I’m not quite at the “l have some cashmere to spin” stage, but I did have some Tasmanian Comeback in my breed study box. The color (as it comes off the sheep, I believe) was dead on, so I decided to give it a try. I took a little bit of my 1 oz sample and tried to spin it fine enough to work for this purpose. I did it short forward draw, and ended up with a relatively firm and smooth yarn.

You can see the little hole under the yarn there. The mending yarn I spun was a bit heftier gauge than the original, but I decided I could work with it. After a first failed attempt at weaving the stitches back together with a darning needle freehand, I realized that the thing to do was to pick up the loose stitches on either side of the broken thread and Kitchener Stitch them back together. Of course I failed to take pictures of that part, but I used two Size 0 double pointed needles and ran them through the dropped stitches, as well as a few stitches on either side. That covered the ones that were about to unravel. A little Kitchener later, and voila! No more holes.

It’s not perfect, but overall I was really pleased with how it turned out. And honestly amazed that the yarn worked for the intended purpose! I usually just spin to spin, but to have a plan and be able to execute it was pretty cool.

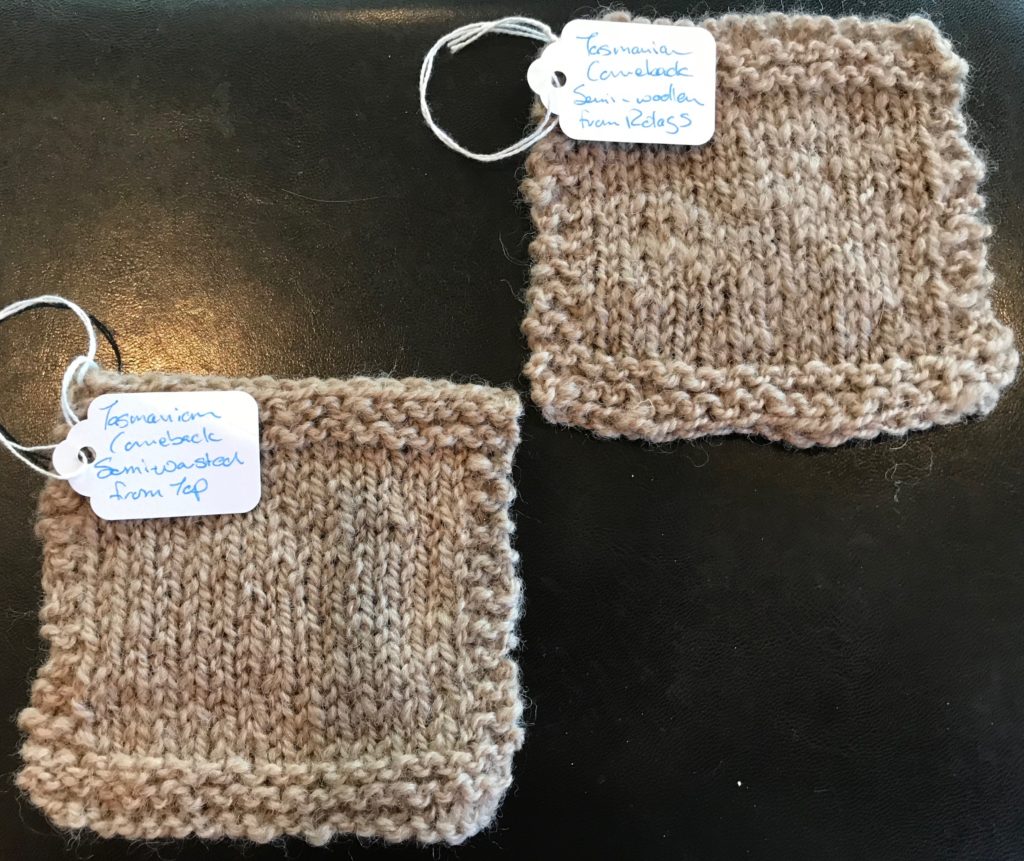

You can see the leftovers of my mending yarn on the bottom here. I split the top the usual way for my other two samples – half for a semi-worsted yarn and half for a semi-woollen. I was very pleased with how both of the samples turned out. The difference between the semi-worsted and semi-woollen samples was very clear, and the swatches were noticeably different too.

The semi-woollen sample is fuzzy and lofty and light, while the worsted sample is just a bit denser and smoother. The semi-woollen yarn I made would make a fine shawl or other garment that wasn’t going to get a lot of abrasion, but I suspect it would pill pretty fast if it got a lot of wear. The semi-worsted yarn would probably still benefit from being spun with more twist than I did If you really wanted a garment to hold up. Although I didn’t knit a sample with my mending yarn, I suspect it’s the most likely to withstand heavy wear. I would work with Tasmanian Comeback again – it’s a soft, relatively fine wool that knits into a nice fabric.

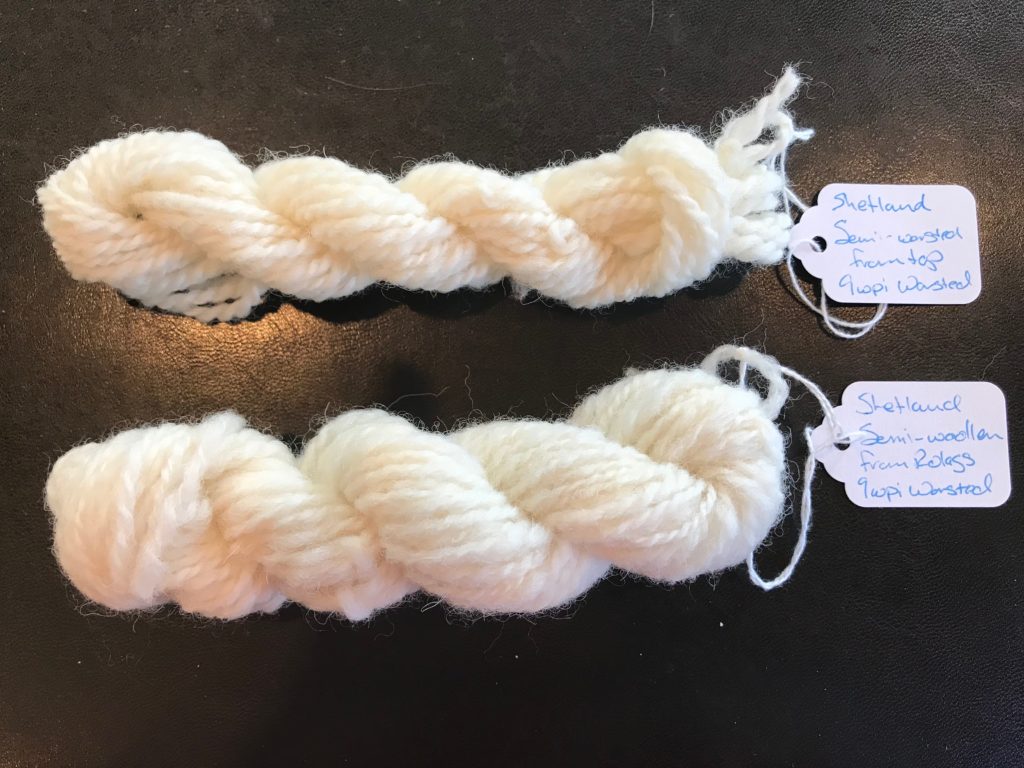

Shetland

My strategy for the breed study has been something along the lines of “go through the box and choose what appeals to me that day.” If I had it to do again, I might have been a little more orderly about it – such as spinning the Shetland and the Icelandic back to back as examples of sheep that can have double coats. I didn’t do that…Icelandic will have to come later. Which is just as well, because I’m pretty sure that the Shetland sample I have is from a single coated sheep or flock.

Shetland sheep as a breed are super complicated and complex, and I’m hardly an expert. It’s very interesting, though, if you’re a fan of sheepy facts – as always, I recommend The Fleece and Fiber Sourcebook as a starting point. Deb Robson does a great job of explaining several facets of Shetland sheep, including why it’s so hard to pin down what a “Shetland sheep” is. Deb is also conducting a long term research project into Shetland sheep – you can keep up with it on her blog over at The Independent Stitch. She also teaches fiber study classes all over – taking one is on my bucket list!

Anyhow…back to my Shetland sampling.

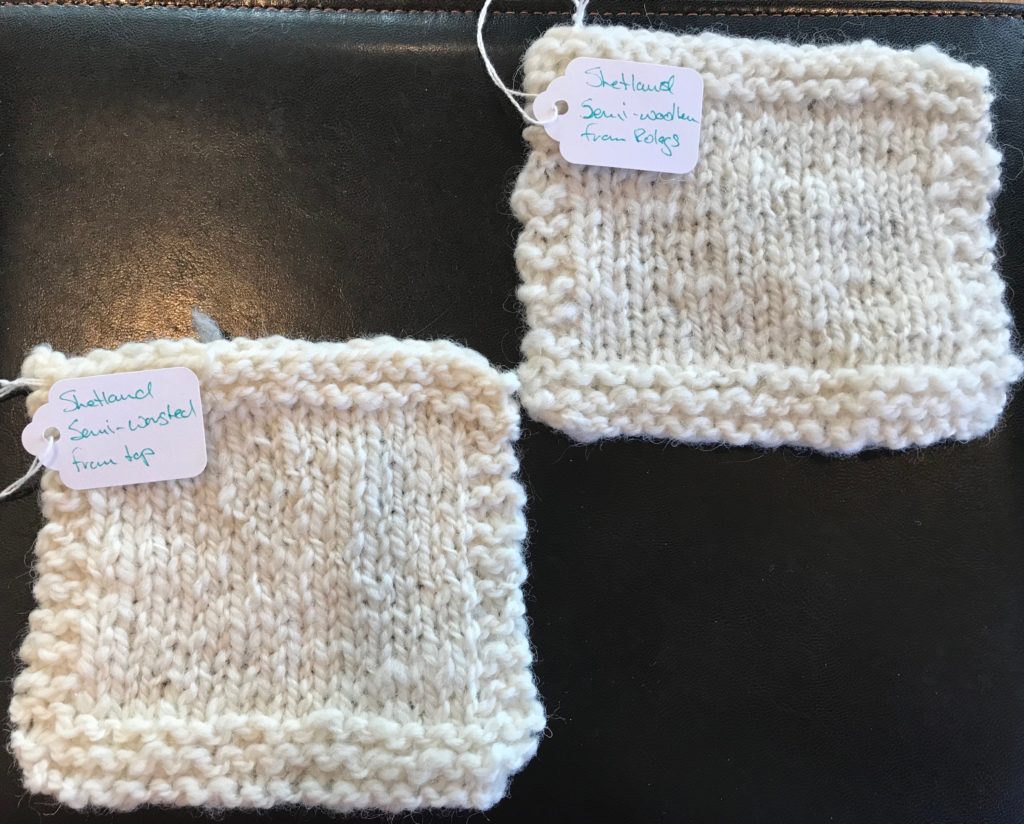

I LOVED spinning the semi-woollen sample long draw, and I don’t often say that. Partly I’m getting more comfortable with the technique (and better at making rolags), but the Shetland was also just the right staple length and texture to draft beautifully. It’s still a little less consistent than I would ultimately like, but I was really happy with how it turned out.

I had a little trouble getting my wheel set up to comfortably spin the semi-worsted sample, which is also unusual for me. I felt like the yarn kept trying to run away from me – my solution was little brake and less twist than I usually put into my singles. I also stripped the top in half so it was more manageable. Once I sorted it out, it was a pleasurable spin!

Both samples were lovely to knit with. The semi-woollen would make a great accessory that wasn’t going to get a lot of abrasion, and the semi-worsted would be a fabulous sweater or cardigan. I think I’ll be spinning more Shetland in the future, partly because I enjoyed this sampling and partly because Shetland sheep are ubiquitous in the Pacific Northwest. Our climate is much the same as the Shetland Islands, so they thrive here as well.

Cheviot

I actually spun a few ounces of Cheviot right after I got my Ashford Joy II – I was excited to try different breeds! I wasn’t paying all that much attention to the breed characteristics though – mostly I was still trying to make my yarn stay together.

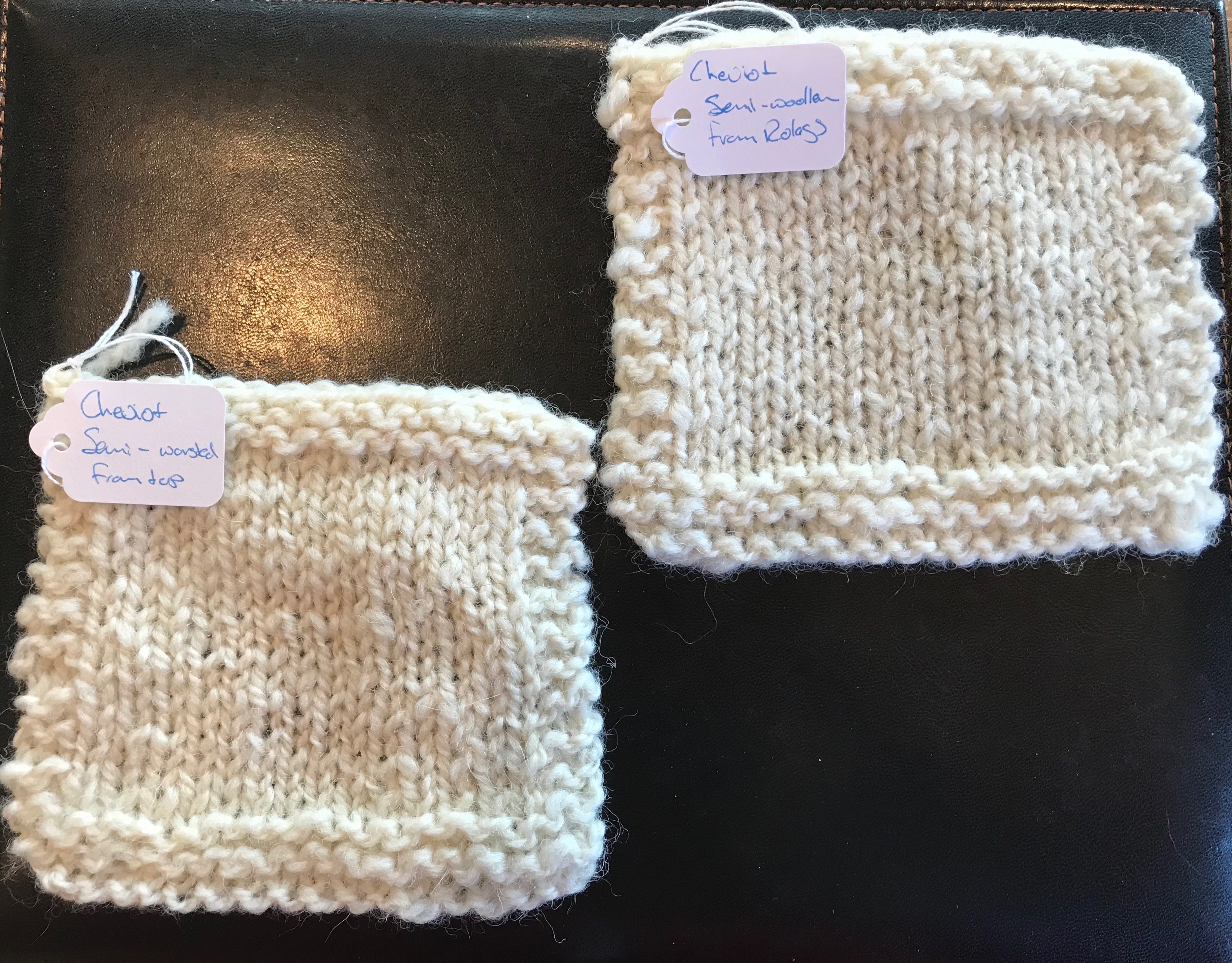

Cheviot sheep are primarily a meat breed, but yield a nice medium wool. I found that it was easy to get too much twist into it – my semi-worsted sample overtwisted quickly and I had to change my technique. Less twist, less brake was the answer here as well. The air in the semi-woollen sample kept that from happening. As you can see, the semi-woollen sample is quite lofty, which kept it soft (relatively speaking). Overall, Cheviot is a pleasant wool to spin.

I wouldn’t say that either of these fabrics are next-to-skin soft, but both would make fine garments to be worn over something else. Although I can tell which is semi-worsted and which is semi-woollen, this is another fiber where the distinction between the two isn’t quite as clear as with, say, the Rambouillet. I’ve found it interesting that sometimes the difference is much easier to discern by touching the yarn or fabric than by looking at it.

You may have noticed that my samples are not all the diameter and don’t work up at the same gauge. This is at least partly deliberate. First, I’m trying very hard not to get stuck in a rut where I spin to the same diameter all the time. Second, I’m letting the fiber do what it’s going to do to some degree. I’m finding that I’m spinning my larger projects finer, trying to exercise my skills that direction, so doing some of my breed study at a larger gauge is exercising those skills. What fun to have so many ways to play with fiber!

Do you have a favorite way of keeping from always spinning your “default yarn?” I’d love to hear about it in the comments!

Alison, if you ever want an Ultimate re-Knitting Project, I have a problematic Icelandic sweater. Sleeves are too short, collar is too tall, eek. But it’s pretty colors and VERY warm, I’d love to actually wear it.

Let me know if you get bored and want to try it!

I’ll try to remember to at least take a look at it next time I’m at your house!